Caricaturing free will

In March 2012 Sam Harris released a short book on free will. The reception was mixed. Especially philosophers dismissed the book as shallow and misguided. Daniel Dennett published a derisive response to it, which Harris posted and replied to on his blog. Meanwhile, there are still those who think the book is a valuable contribution to the debate on free will. I think that is worrisome, because Harris misrepresents the free will debate and the strength and context of scientific evidence. In this post I list three major problems with Harris’ book and take on free will, also going by his blog posts on the subject.

Problem #1: defining free will by a particular position on free will

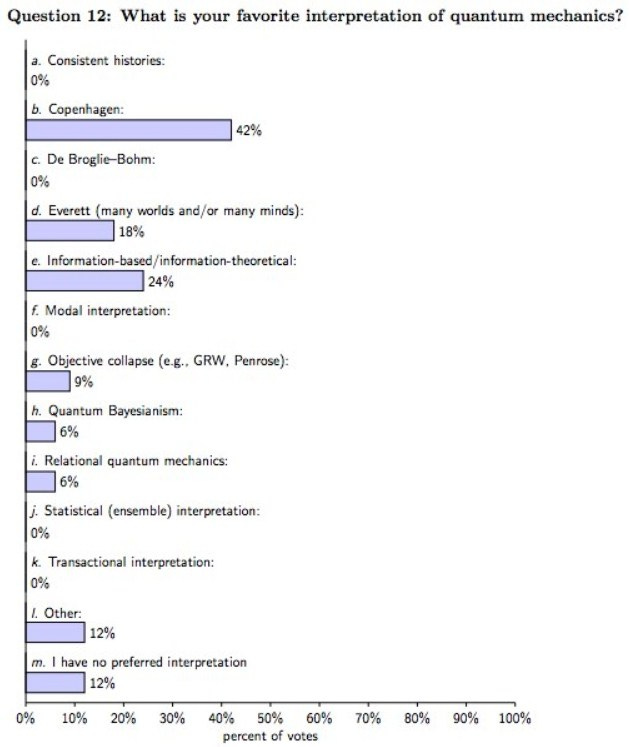

When investigating free will, philosophers are concerned with the following question: “Is our will free in any meaningful way?”. Nothing more, nothing less. The question has been debated since the very beginning of western philosophy (in different terms) and throughout the historical debates many positions have been developed. Metaphysical libertarianism is merely one of these positions. Unfortunately, this is the position Harris caricatures only to present it as the canonical definition of free will. He then attacks this caricature in order to dismiss the entire domain of inquiry. Here is an analogy with another field that might make clear why that is problematic. If you are unfamiliar with quantum mechanics, suffice it to say that the interpretation of quantum mechanics is a contentious issue. Physicists are divided on it. Here is a bar graph of the division:

Imagine Sam Harris were to write a short book on quantum mechanics in which he would equate the Copenhagen interpretation with quantum mechanics as a whole. Imagine he would set out to debunk the Copenhagen interpretation, to then claim quantum mechanics itself is debunked. He would insist that quantum mechanics is not coherent, because one interpretation isn’t. And that those who believe in it are simply trying to hold on to their intuitions. He would suffer the same well-deserved derision from physicists as he has suffered from philosophers for his free will book, were he to go by such a premise, for it would be a very odd thing to do, to say the least. He would not be able to honestly say that quantum mechanics is just a non-starter, philosophically and scientifically. Yet this is what he has done referring to free will:

As it happens, only 12% of philosophers identify (Survey from 2009) with libertarianism. And these are sophisticated technical positions, not the caricature Harris presents in his book. They are neither dominating nor historically primary. Sam Harris writes as if he has debunked free will: “Free will and why you still don’t have it” is one of his blog post titles. Yet he has done no such thing. His engagement with the literature constitutes briefly mentioning compatibilism and psychologizing some of the associated positions as attempts to justify the mere feeling of being a freely choosing agent, while still not being one. These attacks on a caricature of a single position on free will, cannot, in principle, invalidate the possibility of our will being free, as Harris would have us believe.

Problem #2: intuitions on folk intuitions

Sam Harris justifies his caricature with the claim that it is what most people believe. Is it? This paper investigates precisely that, and it turns out people’s intuitions on free will are not that straightforward and naive. Sam Harris tells us what people believe, but never justifies why he believes this is what people believe. This seems to be nothing beyond his intuition about people’s intuition presented as fact. What is actually the case is that what people believe regarding free will depends on the context. Confronted with specific scenarios, people will display strong tendencies to believe in a folk version of hard determinism, rather than magical and “uncaused” will. Such information are entirely absent from Harris’ writings. So contextualism about free will is another ongoing contemporary debate in philosophy Harris ignores. This is convenient, as mentioning this would only make tearing down his caricature of free will more difficult. We can’t go by Harris’ intuitions on people’s intuitions. He should have gathered evidence instead of making assumptions about people’s intuitions.

Problem #3: cherry-picked literature

Not only does Harris barely engage with the literature, he cherry-picks literature, which he then presents as evidence for his view. The Libet papers from the 80’s are classics, but there has been an ongoing debate on these type of experiments and follow-up research for decades since then. Yet Harris mentions two papers that seem helpful to advance his view, and says virtually nothing about the objections. Libet’s veto caveat is called “absurd” early in the book, with very little further discussion. In fact, this is the tone throughout the rest of the book, which is marked by Harris’ perpetual bewilderment: “I cannot imagine”, “I do not know”, “It just happens”, etc. Unfortunately, to know what he does not know, cannot imagine or finds absurd, is not very helpful to build any argument.

The problem with this whole setup is that it misrepresents the debate. It’s not a fair depiction of the issues, and writing for a lay audience is no excuse. Moreover, cherry-picking science to bolster this shallow narrative doesn’t do science any favors. Harris gives the impression that the classic Libet papers and the follow-ups are compelling evidence for his case, when in fact there is compelling literature exposing holes in the setup and assumptions of typical free will experiments. Mentioning and discussing these is the bare minimum for any remotely serious work on free will.

To read or not to read?

Harris’ book will not provide you with an education on free will. Nor will it provide you with a strong case for any particular position in the free will debate. There is no real case of “redefining free will” as if some definition is canonical. A coherent definition is what we’re after. If you’re not familiar with the literature, do yourself a favor and read the entry on free will at the Internet Encyclopedia Of Philosophy, the entry at the Stanford Encyclopedia or even the Wikipedia entry on free will. You will learn more from any of these than from all of Harris’ blog posts and his book taken together.